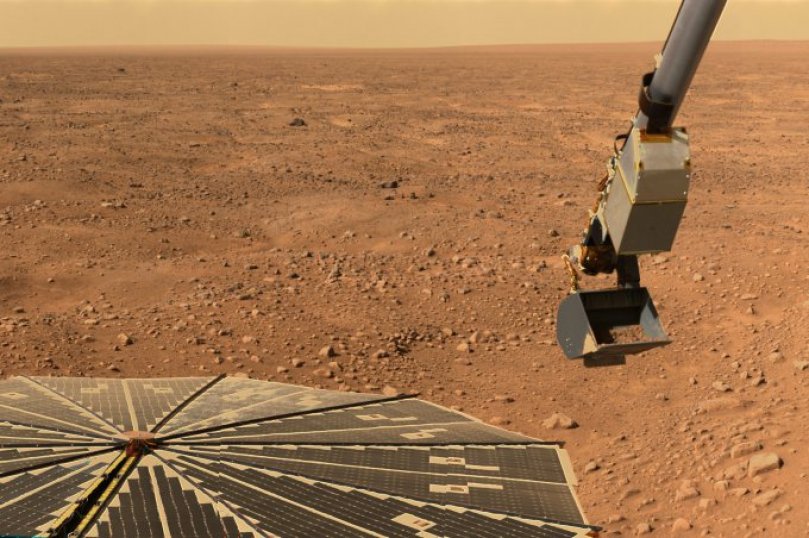

Many new studies from the InSight mission show a dynamic world, inside and out.

Mars may seem dead, dry and cool, but deep underground it is very active.

BERLIN WEATHERIt's a picture shaped by a new series of papers published Monday in Nature Geoscience and Nature Communications, based on data from the first 10 months of NASA's InSight Lander to explore the Red Planet.

InSight landed on Mars on November 26, 2018, and while the mission struggled to bring the "Mole" heat probe beneath the Martian surface, it was quite successful in detecting "Marsquakes" - the equivalent of an earthquake on our planet's neighbors.

"We've finally established for the first time that Mars is a seismically active planet," Bruce Banerdt, InSight's principal investigator, told reporters during a teleconference. "The seismic activity is greater than on the moon ... but less than on Earth."

Banerdt says recording earthquakes on Mars is important because it also allows scientists to better study and understand Mars' interior.

As of September 2019, InSight's seismometer has detected 174 earthquakes on Mars, 20 of which are between magnitudes 3 and 4.

So far, the quakes collected by InSight appear to be much deeper than most quakes felt on Earth, which come from a depth of about 50 kilometers (31 miles). This is about five to 10 times more than earthquakes. Researchers say a person standing on the surface of Mars could feel the strongest earthquakes InSight has recorded, but those quakes would probably not pose much of a threat to anything like a Martian research base or Elon Musk's fantastical metropolis.

In addition to the Mars earthquakes, other InSight data releases issued Monday show evidence of perhaps thousands of swirling wind turbulence or "dust devils" on the Martian surface, paralleling atmospheric turbulence on Mars and Earth, and a deposit of old magnetized rocks beneath the InSight landing site.

"The spectacular thing about these data is that they give us this wonderfully poetic picture of what a day on another planet actually looks like," Vedran Lekic, a University of Maryland geologist on the InSight team, said in the publication.

Nicholas Schmerr, also a University of Maryland professor on the team, says this image could help answer big questions about Mars and whether it can support life or has supported life in the past.

"If it turns out that Mars has liquid magma, and if we can figure out where the planet is geologically most active, that could guide future missions in search of the potential for life.

Comments (0)